A History of Live Programming

The history of live programming stretches back to the earliest days of computing, assuming several different names, and manifesting in different forms: from interactive interpreters to live art performances.

In the past year of 2012, the concept of “live programming” has received broad interest among professional software developers and software engineering researchers. In February, Bret Victor’s CUSEC keynote talk "Inventing on Principle" received over 400,000 views. Victor’s compelling demonstrations of live programming concepts spurred widespread interest, discussions, and followup experiments. In April, Chris Granger’s Light Table project raised $316,720 from 8,000 people through a crowd-funded Kickstarter campaign, and subsequently entered the Y Combinator program. In August, John Resig (jQuery creator) announced that Khan Academy had redesigned their introductory computer science materials to use live programming-like techniques to increase learner engagement.

But where did these ideas come from and where are we headed? We review some of the history and give a list of useful resources and citations at the end.

Classic Era - Interactive Programming

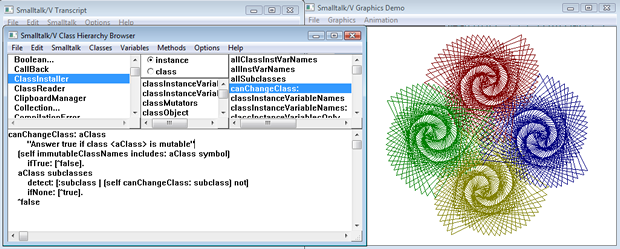

Live programming is an idea espoused by programming environments from the earliest days of computing, such as Lisp machines, Logo, Hypercard, and Smalltalk. In common with all these systems was liveness: Feedback is nearly instantaneous and evaluation is always accessible. For example, any part of the SmallTalk environment could be modified at any time and reflected instantly. Likewise, in HyperCard, the state of any object was considered to be live and editable at any time.

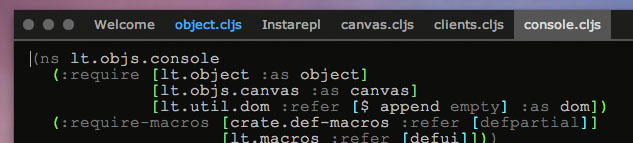

For more recent example of liveness, see the following systems:

Four Degrees of Liveness

What does it take for a system to demonstrate liveness?

Steve Tanimoto describes four degrees of liveness (Tanimoto90): - Level 1: No semantic feedback about a program is provided. - Level 2: Semantic feedback is available on demand on a selected component. For example, typing in an expression in an interpreter demonstrates level 2 liveness. - Level 3: Incremental semantic feedback is automatically provided with an incremental program edit. For example, a spreadsheet supports level 3 liveness. - Level 4: In addition to level 3, incremental semantic feedback is automatically provided for other data events such as mouse clicks or exceptions.

For Steve, liveness is about interacting with a running system that is not stopped while waiting for new program statements. The motivation of liveness is to make data streams in a program visible. That is to visualize how data flows throughs a program beyond the stop-motion model we typically interact with.

But are there other ways to think of liveness? Perhaps, there are other dimensions to be defined and explored.

LIVE CODING

Hacking, art, and performance has been with computing since the 1950s.

Breaking out of the demo-scene of 70s to 90s,

where demo programs of graphics and music were swapped and shared,

emerged a public art form where the graphics and music were created real-time in live programming environments.

Over the last ten years, musicians and visual artists have been applying software engineering skills and constructing their own live coding environments and languages. Live coding in the arts draws on approaches to state in SmallTalk and Lisp a great deal, and persistence and process history is a key research topic for building live coding environments and languages. For example, check out the Circa language.

Although mainstream software engineering research may have ignored it, live coding has been common practice for a long time, in creative situations such as games development, film animation, interaction design, education and music, and in end-user programming contexts in spreadsheets, engineering, statistics and shells.

But, live coding is more than performance. Although people generally think the "live" in live coding refers to a live audience, there are examples of live coding which are reactive to the environment. For example, see this impressive art installation.

Can we think of software engineering activities such as katas are performances in much the same sense as audiovisual performances? Where does art end and programming begin?

For an intensive overview of live coding, including past events, and research see toplap.org.

Software Visualization

The past two decades has seen various approaches for visualizing the source code of a program.

Examples include SeeSoft, visualizing all the source code lines of a program, and CodeCity, rendering a program as a sprawling metropolis.

However, if we had to make a distinction between visualization and liveness, most visualization views the static state of a program and does not have a complete feedback loop. Other approaches which do visualize the program state fall short of liveness. Consider the classic "sorting out sorting" video pictured above. It does a wonderful job of illustrating how different sorting algorithms work, but it falls slightly short of connecting that to the source code of the algorithm.

Visualization in itself may not support liveness, but many of the ideas and concepts can be extended to do so.

Future

Live programming is not in itself a new idea, but rather a decades long quest for liveness. What does the future of live programming hold?

- Liveness in Education: Massive open online classrooms.

- Next generation debugging tools.

- Liveness in IDEs.

- Cognitive Connections with liveness.

- Live programming with mutliple users.

- More...

Have an idea to contribute? Submit to the LIVE 2013 workshop co-located with ICSE in San Francisco.

Bibliography

- Myers, B. A., McDaniel, R., & Wolber, D.. (2000). Programming by example: intelligence in demonstrational interfaces. Commun. ACM, 43(3), 82–89. doi:10.1145/330534.330545

- Victor, B.. (2012). Learnable Programming. Retrieved from http://worrydream.com/LearnableProgramming

- Tanimoto, S. L.. (1990). VIVA: A visual language for image processing. J. Vis. Lang. Comput., 1, 127–139. doi:10.1016/S1045-926X(05)80012-6

- Church, L., Nash, C., & Blackwell, A. F.. (2010). Liveness in notation use: From music to programming. In Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Workshop of the Psychology of Programming Interest Group (PPIG 2010) (2–11).

- Edwards, J.. (2004). Example centric programming. In OOPSLA ’04: Companion to the 19th annual ACM SIGPLAN conference on Object-oriented programming systems, languages, and applications (124). New York, NY, USA: ACM. doi:10.1145/1028664.1028713

- Wilcox, E. M., Atwood, J. W., Burnett, M. M., Cadiz, J. J., & Cook, C. R.. (1997). Does continuous visual feedback aid debugging in direct-manipulation programming systems?. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human factors in computing systems, CHI ’97 (258–265). New York, NY, USA: ACM. doi:10.1145/258549.258721

Burnett, M. M., Atwood, J. W., & Welch, Z. T.. (1998). Implementing Level 4 Liveness in Declarative Visual Programming Languages. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Visual Languages, VL ’98. Washington, DC, USA: IEEE Computer Society. Retrieved from http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=834482

See also the references posted in LearnableProramming though as Bret remarks studying historical software can be challenging.

blog comments powered by Disqus